Closed-loop disturbance signal estimation

Definitions and motivating example

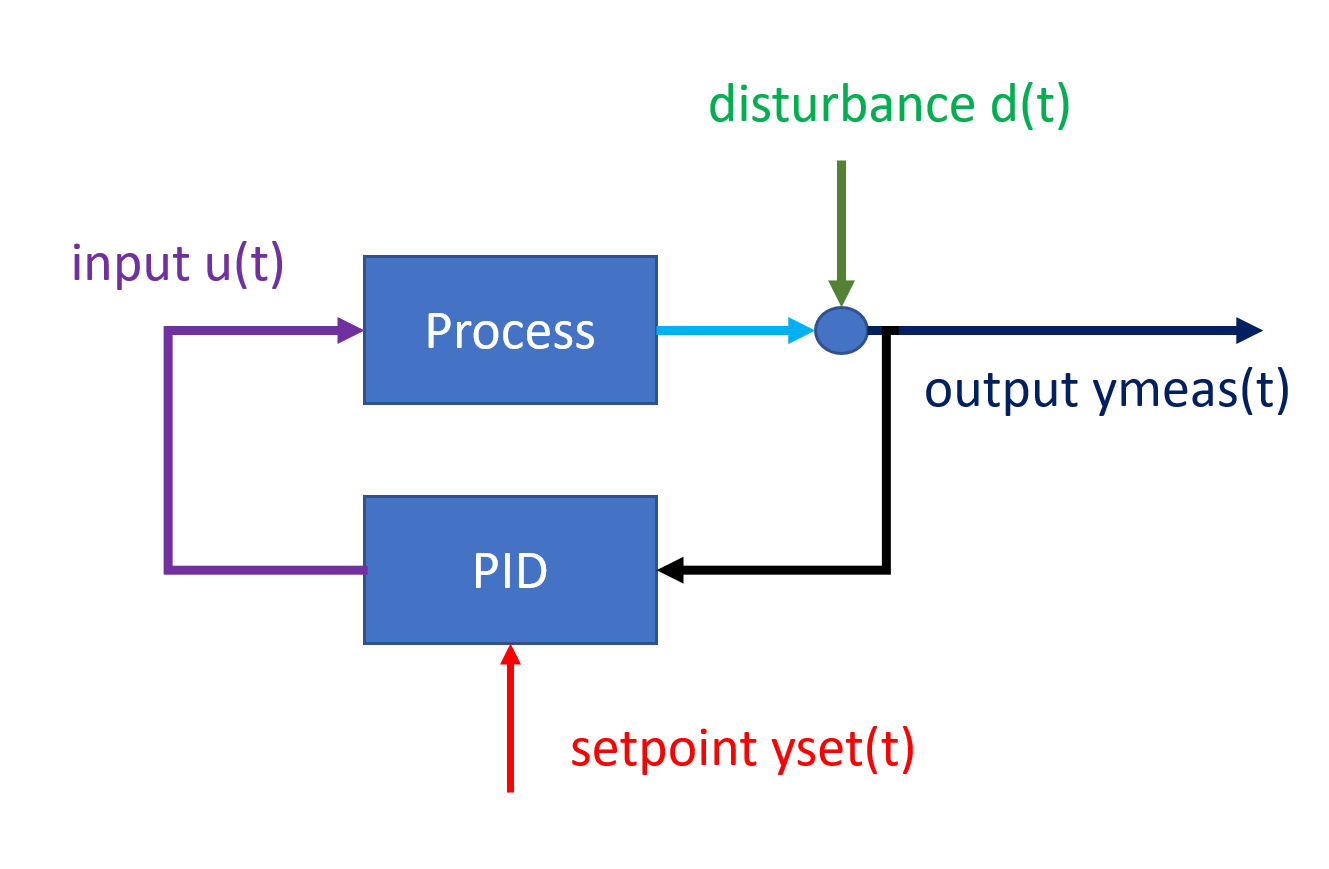

The disturbance is an additive signal that moves the output of the given unit process. Counter-acting disturbances are the very reason that feedback controllers are used, they observe the deviation between setpoint and measurement of the plant output, and change one-or more inputs to counter-act the disturbance.

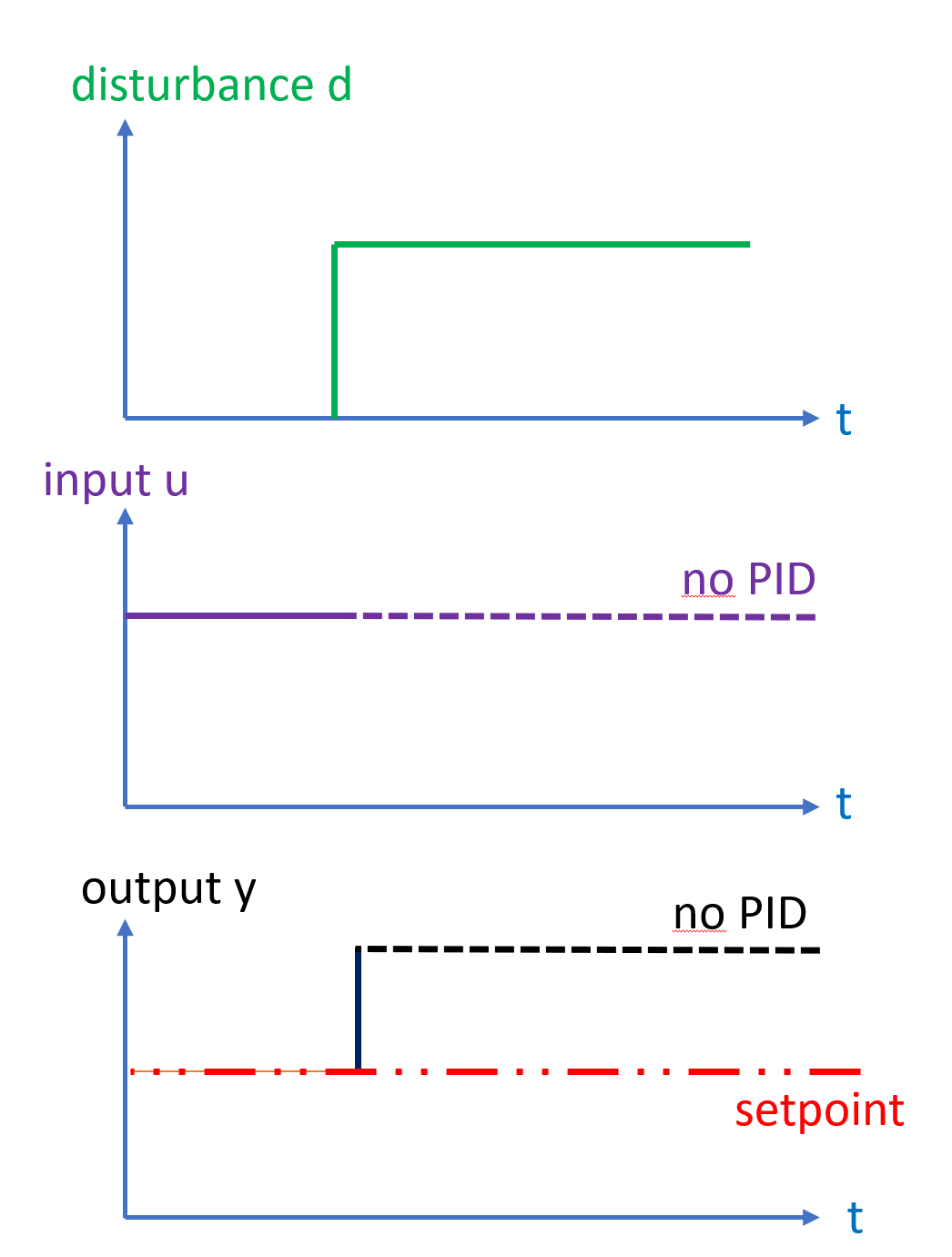

Consider a step disturbance acting on a process without feedback

The feedback is directly fed through to the output, while the input is constant.

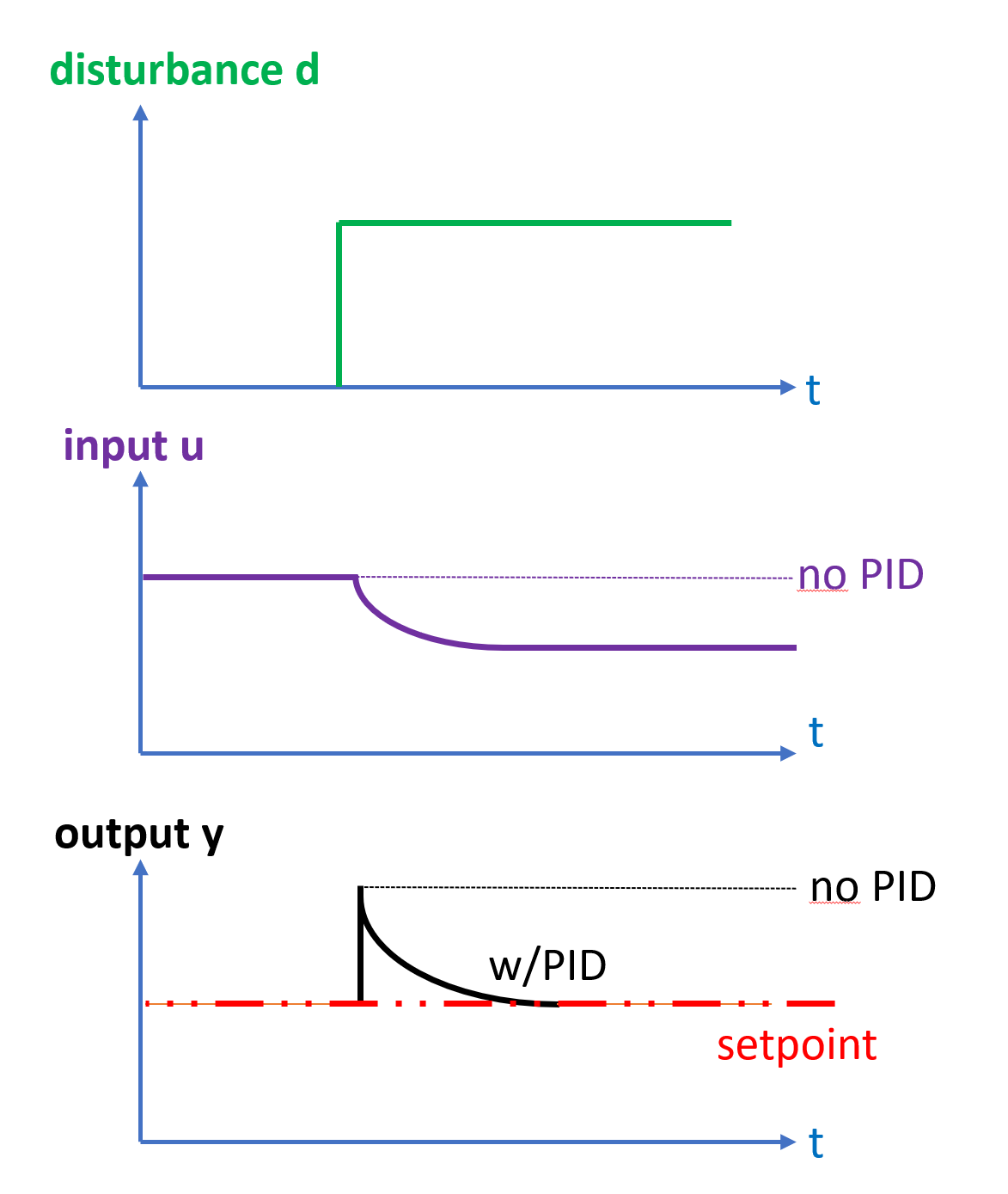

Now consider and compare the same step disturbance, but this time a PID-controller counter-acts the disturbance:

The disturbance initially appears on the process output, then is iteratively with time counter-acted by change of the manipulated variable \(u\) by feedback control, thus moving the effect of the disturbance from the output \(y\) to the manipulated \(u\).

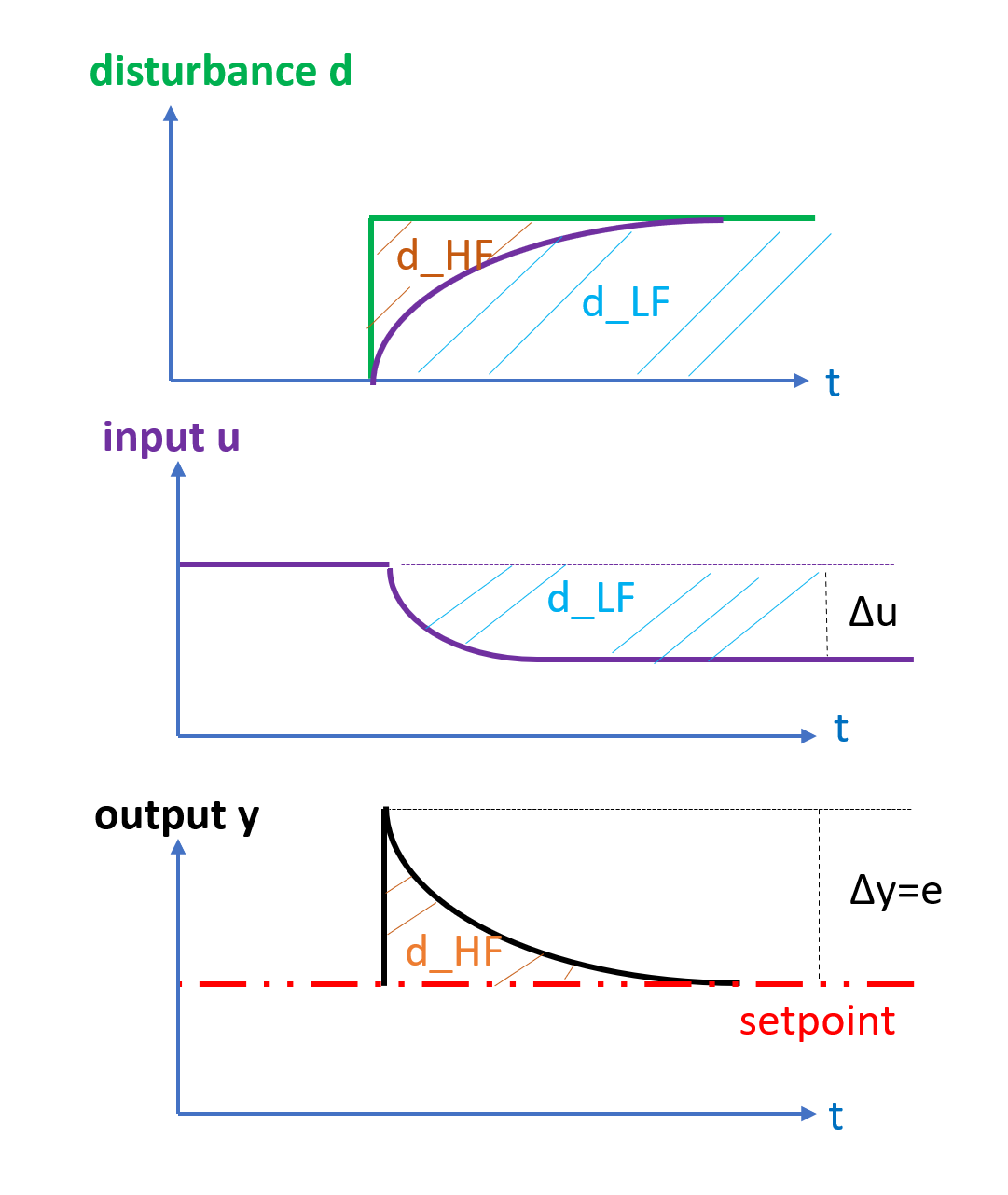

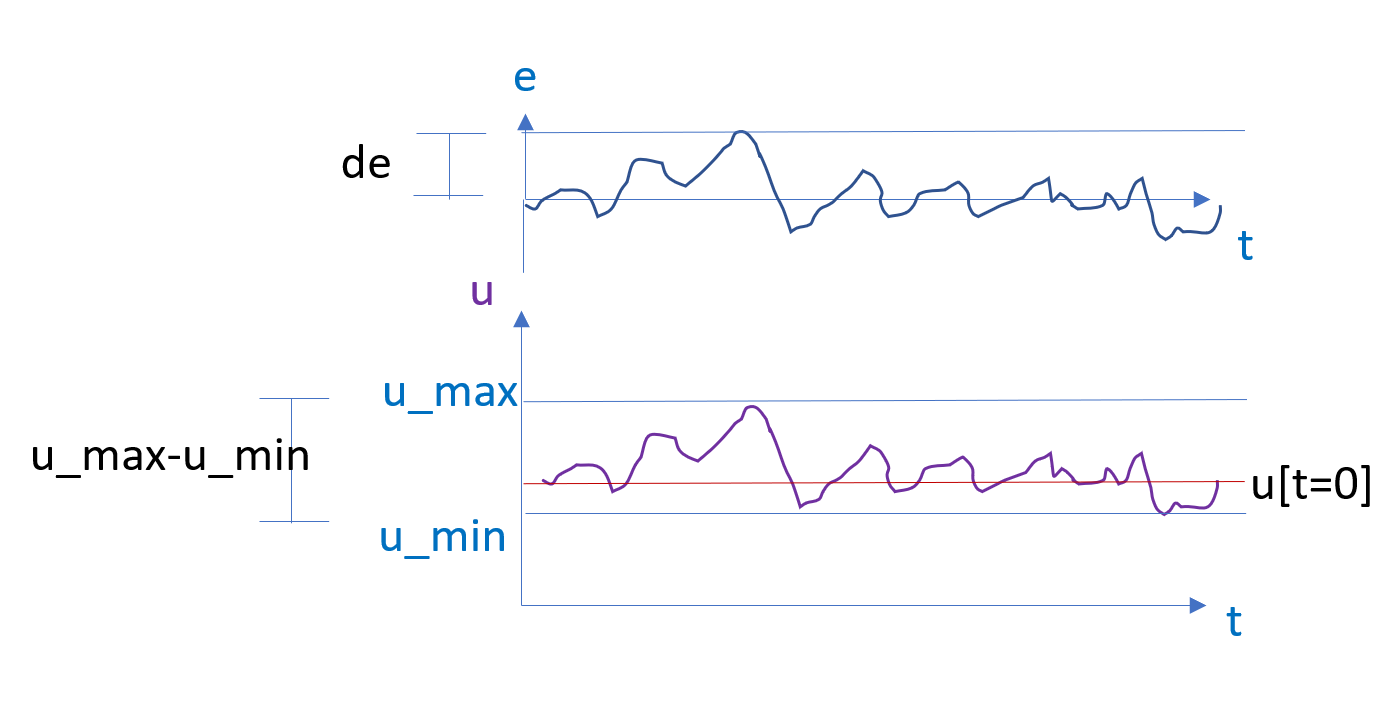

Observing the offset between setpoint and measurement gives a "high-frequency" \(d_{HF}\) response and is seen first, while the change in \(u\) is gradual and "low-frequency" \(d_{LF}\) and the approach will attempt to combine the two as shown below

The aim of this section is to develop an algorithm to estimate the the un-measured disturbance \(d\) indirectly based on the measured \(u\) and \(e\)

Note

Why is disturbance signal estimation important?

Disturbances are the "action" or "excitation" that causes feedback-controlled systems to move. If disturbance signals could be estimated, then a disturbance could be "played back" in a "what-if" simulation and different changes to the control system could be assessed and compared offline.

The measurement \(y_{meas}\) shows us the combination of the disturbance \(d\) and the process output \(y_{proc}\)

$$y_{meas}[k] = y_{proc}(u[k]) +d[k] $$

Note the above convention for \(y_{proc}\), \(d\) and \(y_{meas}\) are consistent with the convention used by PlantSimulator.

This is important, as the PlantSimulator is used in the estimation of disturbances.

If a model of the process can be determined that is close to the actual process output

$$y_{process} = y_{mod}(u(t)) $$

then an estimate of the disturbance is given by

$$d_{est}(t) = y_{meas}(t) - y_{mod}(u(t)) $$

Note

When the process model is known, then the disturbance is implicitly also known

The above equation shows that when the process model is known, the disturbance signal is implicitly known. The tasks of determining the disturbance and determining the process model are one and the same.

What are the challenges?

The challenge in describing disturbances in feedback-systems is that the feedback aims to counter-act the very disturbance which needs to be described by changing the manipulated variable.

Thus, the effect of the disturbance is in the short-term seen on the system output \(y\), but in the long-term the effects of the disturbance are seen on the feedback-manipulated variable \(u\). The PID-controller will act with some time-constant on \(u\),and this change in \(u\) will again act back on the output \(y\) with a delay or dynamic behavior that is given by the process(described by the process model.) To know what amplitude a disturbance has, requires knowledge of how much effect (or "gain") the change in manipulated variable u will have caused on the output \(y\).

In most cases only a single \(u(t)\) is considered, and this is the pid-output \(u=u_{pid}(k)\).

Note

in general it is hard to know if the observed closed-loop behavior \(y_{meas}\),\(u_{pid}\) is due to a process with large process gain and the \(u_{pid}\) responding to large disturbances or if the pid-controller is reacting to small disturbances for a process with small gains.

Observations

- Note that \(y_{proc}\) is not directly observable unless the disturbance is zero.

- \(y_{proc}\) depends on one or more inputs u(t) that are measured.

- one of the inputs to the \(y_{proc}\) is the output of the pid-controller, which looks at \(y_{meas}\) and tries to counter-act disturbances that enter, thus \(y_{proc}\) and \(d(t)\) will be covariant.

It is in general much easier to determine the gain of the process if there is "external excitation" either

- the pid-controller is set in manual mode and a step change is performed, or

- a setpoint step or some other setpoint change is applied to the pid-controller, or

- (if the process is multiple-input, single-output (MISO), then applying changes to the other inputs also appears to improve the estimate of the process gain)

The aim of this algorithm is to give a sensible estimate of the process gain/disturbance even in cases where there is no introduced excitation. In some cases it will be impossible to determine a unique process gain, but in such cases it would be useful if instead the method returned a range of possible values.

Approach

Sequential Gain-Time Constant Identification for Closed-Loop Disturbance Reconstruction

The goal of the method is to find a UnitModel that describes the process that the PidModel is controlling, based on measured time-series data.

The terms in the UnitModel listed in terms of their relative importance are:

- process gain (most significant)

- process time constant

- process time delay (not currently implemented)

- process curvature (not currently implemented,least significant)

Note

All terms in UnitModel are important

Failure to describe time-delays or curvatures may cause poor match in process gains and time constants.

Thus all terms in the UnitModel are actually important.

The method attempts to exploit co-simulations of PidModel and UnitModel in the PlantSimulator, and that these simulations are

- very computationally inexpensive (i.e. can be run numerous times), and

- the simulations can be fully automated.

The method can be classified as disturbance reconstruction, as for each candidate UnitModel a disturbance signal is inferred,

and the closed-loop system is simulated with this disturbance.

Determining the process gain and time constants are coupled. As the process gain has the most influence on the resulting simulations, it is chosen to determine it first.

The chosen approach to attempt to deconstruct this problem is sequential estimating

process gain and process time constant (as opposed to solving simultaneously).

Each sequential step uses a form of global-search or trial-and-error to simulate the system for numerous values, and then attempts to rank

the resulting simulations to determine the most promising estimate.

A large number of synthetic datasets with known solutions are used to guide the design of the algorithm, and to classify the properties and performance of the method:

- step disturbances

- random walk disturbances

- sinusoidal disturbances

- sinusoidal disturbances and a setpoint step change

- step disturbance and setpoint step change

Note

In other parts of the library objective metrics that describe the fit between modelled and measured output are used to select models. In closed-loop, this kind of scoring is much less cut-and-dry, because by our definition, the disturbance signal is all parts of the measured output \(y_{meas}\) that the process model is unable to describe with \(y_{process}\), thus the disturbance signal may include model errors, and usually \(d_{est}\) results in \(y_{meas}=_{process}+d_{est}\), so that the deviation between measured and modelled output (including disturbance) is zero.

The accumulated traveled travel \(Q\) of a signal we defined as :

This metric is used extensively in the below algorithm.

Algorithm outline

This algorithm is implemented in the class ClosedLoopUnitIdentifier, as follows:

given an estimate of the PidModel from prior knowledge or from PidIdentifier:

- choose indices to ignore (bad or frozen portions of data)

- use a heuristic to get an initial static "model-free" guess for the process model (process gain and -sign) (

step0) - set heuristic broad search range for the process gain \([G_{min},G_{max}]\)

- one "pass"

- taking the best current guess of process time-constant, estimate the process gain by a global search between \([G_{min},G_{max}]\) (

step1) - taking the best process gain from step1, estimate the process time-constant(

step2)

- (try to improve the model by testing time-delays)(not implemented)

- reduce the range of \([G_{min},G_{max}]\) around the value found in

step1and do another pass, or exit if pass did not find an improved gain.

- taking the best current guess of process time-constant, estimate the process gain by a global search between \([G_{min},G_{max}]\) (

Note

Convergence

- It has been found that doing 2 passes is usually sufficient to converge(usually a third pass does not further improve the estimates).

- In general the bound on the gain need to be wide enough that the true value is hopefully not outside the initial bounds, but also the wider the bounds the more distance between each attempted gain for a given number of runs. How wide to chose these bounds, and how much to narrow the bounds for the second pass are heuristically set (based on performance in unit tests).

- There is no sense doing a second pass if the steps 1 and 2 did not cause any change in parameters (in which case only one pass is done)

- In general there is no guarantee that a sequential optimization will converge, but the method usually does so in practice if information exists in the data set

- If the data has a insufficient level of excitation, it sometimes happens that the algorithm is unable to produce estimates in step1 and step2 that improve on step0. This is a strong indicator that identification should be re-done on another dataset at a later time.

Note

Outstanding issues of ClosedLoopUnitIdentifier

- the method does not use the supplied

FittingSpecsto select indices to be ignored based on user-supplied minimum or maximums in inputs or outputs. - the outlined final step of refining the identified model to also determine a time-delay is not implemented

- the method could conceivably be extended to include identification of even nonlinear process model terms, but this is not implemented.

Step 0

The first, model-free estimate of the process gain

The idea of the initial estimate gain is to get an idea of the approximate value of the process gain, which will determine the bounds for global search in subsequent steps.

A model-free estimate of the disturbance is required to initialize subsequent sequential estimation.

For the first iteration, all process dynamics and non-linearities are neglected, a linear static model essentially boils down to estimating the process gain.

Let the control deviation \(e\) be defined as

This first estimate of the process gain \(G_0\) in a linear model \(y(t) = G_0 \cdot u(t) + b\) is found by the approximation

The PID-controller integral effect time constant meant that a peak in the deviation \(e\) will not coincide with the peak

in \(u\).

The idea of creating an initial estimate with min and max values is that it circumvents the lack

of knowledge of the dynamics at this early stage of estimation.

Given the gain an initial UnitModel is created with a rudimentary bias and operating point \(u_0\), so that the model can

be simulated to give an initial \(y_{mod}(u)\), so that an estimate \(d_{est}(t)\) can be found.

Note

Step 0 dynamic artifacts in the estimated disturbance

Because no process dynamics are assumed yet, \(d_{est}(t)\) at this stage will include some transient artifacts if the process has dynamics. \(d_{est}(t)\) will be attempted improved in subsequent steps.

It has been observed in unit tests that this estimate in some cases is spot on the actual gain, such as when the disturbance is a perfect step.

It seems that the accuracy of this initial estimate may depend on how much the process is close to steady-state for different disturbance values, as disturbance step produces far better gain estimates than if the disturbance is a steady sinus(so that the system never reaches steady-state.)

Step 0: Guessing the sign of the process gain

Methods for open-loop estimation when applied naively to closed-loop time-series often estimate process gain with incorrect sign.

The reason for this is that cause-and-effect relationships are different in closed- and open loop.

It is thus important to use an identification algorithm that is intended for closed loop signals, and to also include information about the setpoint \(y_ {set}\) to the algorithm, so that the algorithm can infer about the control error \(e\).

Note

Counter-intuitive input/output relationship in closed-loop systems

As an example, if inputs \(u\) and output \(y\) increase in unison, you would in the open-loop case assume that the process gain is positive. In the closed-loop case, the same relation between input and output change is often indicative of a negative process gain. In the closed loop, a disturbance enters the output \(y\), is counter-acted by the controller output \(u\), so an increasing \(u\) in response to an increasing \(y\) would be because the sign is negative. The inverse is also true, what appear to be negative process gains at first sight may in closed-loop be positive process gains.

The strategy that is employed by the algorithm is to require the PID-parameters to be identified prior to running the closed-loop identifier, and to use the sign of the Kp in these parameters to set the sign of the process gain.

Step1

The initial guess for the process gain and process gain sign above have not considered the pid-controller and its dynamics, including any setpoint changes that the dataset may contain.

Step1 is different if there are setpoint changes in the given dataset versus when there is not, as described below.

in the case of setpoint changes

The PID-model and process model is simulated for a given gain \(G\) in a closed loop with no disturbance acting on it, but where the actual setpoint

signals and any external model inputs u are applied. This results in a simulation of what the output $y_{meas}$ would have been if the disturbance was zero

This gives an disturbance-free (adjusted)pid-output \(u_{pid,adj}\)

It has been observed that the process gain \(G\) that results in the smallest \(Q(u_{pid,adj}(G))\) is a good estimate of the true process gain in unit tests where the true gain is known in advance.

Note

The above works equally well in the case that process to be simulated is a multiple-input system and the other non-pid inputs are changed during the tuning set.

in the case of no setpoint changes

If there are no setpoint changes, the above method of determining the process gain will not succeed, as the objective function will be flat.

In this case, the global search instead attempts to find the process gain that results in the disturbance that "travels the shortest distance", expressed as:

Note

- this method is heuristic

- the objective usually has a minimum, but not always (such as if the disturbance is a perfect sinus in unit tests)

- the objective space is fairly flat, the minimum has a fairly low "strength", i.e neighboring process gains have almost equally low objectives

- the objective space seems to be more concave ("stronger" i.e. more significant minimums) when the process gain is higher.

Step 1 algorithm:

- given an initial process model (with a zero or nonzero time-constant) and an estimate of the PID-model(including \(K_p\))

- given a range \([G_{min}, G_{max}]\)

- for a number of gains \(G\) between \(G_{min}\) and \(G_{max}\)

- calculate the resulting disturbance \(d_{est}(G)\) and \(u_{pid,adj}\) (using

PlantSimulator) - calculate \(Q(u_{pid,adj})\)

- calculate the resulting disturbance \(d_{est}(G)\) and \(u_{pid,adj}\) (using

- chose the "best" gain by a number of criteria

- "v1": if setpoint is flat and no other inputs, chose the gain that minimizes \(Q(u_{pid,adj}(G))\) (unless solution space is flat)

- "v2": if the setpoint is changing chose the gain that minimizes covariance between \(d_{est}(G)\) and setpoint(unless solution space is flat)

- "v3": if the is more than one input chose the gain that minimizes covariance between \(d_{est}(G)\) and other input(unless solution space is flat)

- "v4": if solutions space for the above three are all flat, chose the gain that minimizes \(Q(d_{est}(G))\)

Note

Better estimates when set-points change

The algorithm seems to in general give better estimates of the process if there are step changes in the external inputs or in the pid-setpoint, and the algorithm appears to be able to handle both cases.

Step2

If the process is actually dynamic yet is modeled as static, then the above methodology will result into un-modeled transients bleeding into the estimated disturbance, where they will appear as "overshoots", 2.order dynamics in the estimated disturbance. These un-modeled transients may cause process gains and disturbance estimates to be skewed slightly too large, unless the transients can then be modelled

Note

The applied principle for determining process time constants in close-loop

If every change in \(e(t)\) is followed by similar transient in \(d(t)\) then this is a sure sign that there is un-modeled dynamics, if these "transients" can be described by adding dynamic terms to models and this causes a "flatter" estimated disturbance, then this is usually preferable.

In step 2, the model found in step 1 is modified by attempting to add add larger and larger time constants to the identified model, and analyzing the accumulated absolute travel \(Q\),

for the estimated disturbance vector \(d_{est}\).

Step 2 algorithm:

- given an initial process model (with a nonzero process gain)

- if first pass:

- start at \(T_c=0\)

- while the \(Q(d_{est}(T_c))\) keeps decreasing:

- calculate \(d_{est}(T_c)\) for the given \(T_c\) (using

PlantSimulator) - increase \(T_c\)

- calculate \(d_{est}(T_c)\) for the given \(T_c\) (using

- for subsequent passes:

- seek through \(Q(d_{est}(T_c))\) for [0, T_{c,pass1}] (using

PlantSimulator) - choose the \(T_c\) with the lowest \(Q(d_est{est}(T_c))\)

- seek through \(Q(d_{est}(T_c))\) for [0, T_{c,pass1}] (using

Side-note: Alternative method to estimate process gain based on \(d_{LF}\)

Refer to the example at the top of this section.

The disturbance can be imagined as having two distinct parts:

- a high-frequency part \(d_{HF}\) that depends on \(e(t)\), and

- a low-frequency part \(d_{LF}\) that depends on \(u(t)\) and it is assumed that

There are essentially two ways of calculating the disturbance

- By subtracting the modelled \(y_{proc}(\hat{u})\) from \(\bar{y}\) : \(d_{est} = \bar{y} - y_{proc}(\hat{u})\)

- By \(d_{est} = d_{HF}(\hat{u}, y_{set}) +d_{LF} (u)\)

where \(d_{LF} (u) = \hat{y}(u(t))- \hat{y} (u(t_0))\)

Note that \(d_{HF}\) does not change with changing estimates of the model gain or other parameters, while \(d_{LF}\) does.

The algorithm in the above sections struggles most in the case that the disturbances are relatively flat, while there are no setpoint changes, so that there is a general lack of excitation.

In those cases \(d_{LF}\) may be small, and so it may be possible to aid estimation by assuming \(d_{est}(t) \approx e(t)\) or even \(d_{est}(t) \geq e(t)\)

Performance, conclusions and further work

In unit tests summarize the expected performance for different types of use-cases

- step-disturbances accuracy to within 5% is for static processes and 10% for dynamic processes are typical

- random-walk disturbances accuracy to within 12-25% for static processes, but very poor accuracy for dynamic processes.

- sinus-disturbances poor accuracy for dynamic and static processes.

- the method is able to remove data points to be ignored from the analysis (bad data points) and still succeed

- the method does well even for multiple-input systems provided that there is excitation in the non-pid controlled inputs (in fact this appears to make estimation easier.)

Conclusions

- The algorithm seems to work well on certain types of common disturbances where the process is close to steady-state but then intermittently is excited (

step disturbances). - The algorithm struggles if the disturbance is so "rich" that the system in fact never reaches steady-state(such as in the case of a random-walk or sinus).

- In situations where the algorithm does poorly, the algorithm is usually not able to improve on the

step0initial estimate, typically because global search does not reveal any minimum in any of the considered metrics inpass1. - If the method is unable to improve on the

step0, it is recommended to re-identify the model on other data until the algorithm converges over two passes.

Further work

- look into the unit tests where it is attempted to estimate multiple-input single-output systems with non-zero disturbance.(

Static2Input_NOdisturbanceWITHsetpointChange_ExtUChanges_detectsProcessOk)